Once I was revered as Master of the World.

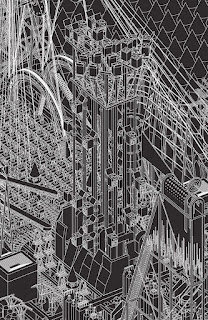

Upon Mount Ty'Ryluan I occupied the throne within the immemorial fortress Surcort. Here was a castle and keep which riddled the oppressive lone mountain with its tunnels and great Warrior Chambers and which was the very center of my vast empire. I can claim with good conscience that in my day Surcort housed the most heralded gentlemen and valued peoples of all these once-fair lands, as had it always since its construction several ages agone. Before I impart to you the grievous tale I have to tell, I beg you: Grant me a single moment to recall the glories of my stronghold in the mountain, for these memories are all that remain of my beloved home...

Mount Ty'Ryluan--called by our distant ancestors the Old Red Rock--alone rose from the unbroken and tossing grassy lowlands, a solitary and misplaced bulk of scarlet stone. It soared higher than all other mountains in any visited land. About its midsection clouds would coil; its peak could puncture the black tapestry of night. And there upon, the founders of my once great empire set the first stones of Surcort.

Around the base of the mountain was erected a curtain of sheer stone, with forty and eight strong watchtowers. To walk this wall's measure the most fit man would require a full day, from dawn to downing. A single gate along the length of this impenetrable curtain of defense was placed on the western-most face with beetling turrets overlooking the Darwell Bottoms. It admitted residents and guests at regular intervals; otherwise, the great gate remained closed and was dutifully guarded by a hundred of the finest soldiers of the realm. Embedded in the wooden doors of the gate were skulls from a thousand foes vanquished, a grim but rigid reminder of the empire's bloody history.

Halfway up the mountain from the thinly forested valley surrounding it, set upon a sprawling ledge, was the castle which was both my country's heart and my home. It was enveloped by a second smaller perimeter wall which ran along the outer ledge of the stony shelf. The Walk of a Thousand Steps Four Times Over connected the lower gate with this ledge. Of these, the first and second thousand steps were carved out of the mountain stone; the third thousand were inlaid slabs of glossy black xirum ore; the final segment was of pure and gleaming yarviz, mined in the northern tracts of the Wailing Mountains. The stairway was a narrow and treacherous path, but the mountain was too steep to be ascended at any place other.

These things I take care to describe, for these things shall be seen never again. Alas, proud Surcort, the castle and keep raised over the course of a dozen generations and built at the cost of a dozen plundered nations' treasuries and ten thousand labor slaves, now is lost.

It is from Surcort I ruled, from the tallest of the Eight Towers wherein lay the Divine Hall. A fierce warrior had I been--not even mildly similar to the coughing, trembling coward that now imparts this tale--for I fought and killed my way into that hall of greatness where I demanded and earned the respect and loyalty of an empire.

Aye, this you must know: In Surcort, never was the child of the reigning family the unquestionable heir to the throne just as royalty was never determined solely by the crest of a family. To rule in Surcort, one had to be a champion and conqueror, and that I was.

Cussurak was my adversary when I came of age and when the old Master of the World had gone on to Ty'Ryluan's peak to reside with the Creator Lords. Cussurak was of the late ruler's blood, and he fancied himself rightful heir and unopposed. But I had spent many of my days in battle alongside his father, and I proudly boast that he and I shared in more than a hundred campaigns and quests. Cussurak the Younger accompanied our army on perhaps ten such crusades, and rarely could he be found on the battlefield. Nay, Cussurak the Younger was more apt to be captivated with his endless studies and with spilling over his forebear's vast libraries than he was with battlelust and farflung adventure.

So it was that upon the passing of Cussurak the Elder, I knew I could not squander my services on the likes of his impotent progeny. I felt truly the empire would simply rot should he attain the throne. Thus, drawn to action by my undying and blind love for the homeland, I challenged him. On the Field of Providence before an assemblage of nobles and officers and peasants from provinces near and far, and after a short and savage duel which was surrounded by much pomp, I slew Cussurak the would-be-ruler.

May the Creators pardon me that tragic venture, be it out of their mercy or for my ignorance. For, had I known what was to come, I would not have sought to oust Cussurak. Mistake me not: It is not that it is extraordinary for one to be slain on the Field of Providence, for it is written that those in contention for the highest throne in the land must be willing to have their souls cleaved from them...and certainly it is not that the people were unwilling to accept me as Master of the World, to which I can attest unequivocally.

For ten years I trod these lands as Master of the World. The Tome of Rathnic shall credit me with the acquisition of the western lands B'lai and Fastead Heath. My legions crushed the savage Morrt tribes and laid siege to Kutha, City of the Dead, when its armies threatened to march on the Solva Province. And around the Ty'Ryluan valley, in those green hills and woodlands, a dozen new villages emerged whilst the farmlands flourished. During the first four seasons I bore the crown, the number of residents at my Surcort increased eight-fold. Strong were we, and proud.

Had there been a force without willing to assault the impossible walls of Surcort, or face the seasoned army within housed, I would have laughed at their foolishness. But the threat did not come from without. When the darkness unfolded, it crept from beneath our feet. It seeped out of the mountain itself.

As the number of Surcort residents multiplied, so Surcort had to expand. No room remained on the ledge for additional structures...and it was unthinkable to build on the side of the mountain, a feat that would take ages of labor and the most advanced designs. I was left only one practical option: The maze of tunnels in the mountain would have to be extended.

And I, in my vanity, believed it was my good fortune that during my lifetime, when I served as a warrior in the elder Cussurak's army, I had been active in the annexation of an isolated coastal region on the fringes of our frontier called Amoria. The Amorites were regarded as engineering masters, and at my invitation, Surcort hosted a contingent of their prized citizenry. Under the hands of these wonder-working architects the excavation went deep into the rock, and hollow shafts were cut down through Ty'Ryluan to levels even below the valley floor. Five years of work, and a network of hallways and rooms spread through the rock and branched and scattered beneath the plains. The system was far superior to any of the original Warrior Chambers...it was so complex, no one Amorite engineer was familiar with all the twists and turns and hidden halls. I can now but wonder if this marvelous feat was in some way an act of vengeance upon the empire which enveloped the Amorite civilization...

For, it is in the deepest, most remote corners of the tunnels that our ruin came to life. The Creators themselves could not have known of so powerful a legion lurking in the sand and stone, waiting to emerge a deadly adversary to man.

How I detest the series of events I unintentionally caused to occur. Alas, I have learned that had I been slain on that Day of Contention in place of Cussurak, Surcort's walls and the cliffs of Mount Ty'Ryluan would not be strewn now across the valley like the corpses of a vanquished army...and those who abided there might not be fodder for the evil, misshapen bastards of pitch known to men as the Blackk Gor. And had I not ordered the construction of the tunnels, the remaining people of this collapsed empire--and all other races which may exist beyond its boundaries--would not now face probable annihilation.

The Blackk Gor, disfigured behemoths that roamed the Pit, we thought to be no more. I, myself, led troops into battle against them nigh four moons past my ascension to the throne. We marched into that befouled cavern of the Pit and fought till all the Gor we found were writhing in pools of black blood beneath our feet. To this day I recall the wails of the dying monsters flooding the cave, poisoning our ears...I recall the pride I shared with my soldiers over the carnage, certain that our victory was final. No more, I proclaimed to the regiment, would the Blackk Gor hunt the mountain folk nearby the Pit; no more would they raid villages in their thirst for mortal flesh and meat.

But the Blackk Gor did not die that day. Nor shall they ever die, for what does not live can not be slain.

Those pools of black we mistook for blood, I have since been told by wandering Dassmen and sorcerers, were in fact pools of souls. The rugged, gray skin, which our swords hacked at with great difficulty was not flesh, but animated rock. And the screams of the Gor were not vented for the agony of death. No, those screams were their frenzied vows to return.

I, and my army, traveled two days on horseback to return to the victory feast at Surcort. It took the company of Gors nine years to get to Ty'Ryluan. Their fluid souls crept sluggishly through the ground, gradually strengthening, compounding both their number and their hatred. By the time they reached the valleys around Ty'Ryluan, the tunnels I had commissioned were already built. As can be guessed, these labyrinths only aided in their offensive.

As soon as they surged forth from the ground, they regained solid form. There was naught to be done. My armies fell, battling in the maze, as they became disoriented and separated. The Blackk Gor had more than tripled in number, so that even had we met on an open battle field, the odds would favour us only marginally. The enemy did not need strategy, for they moved through the halls and walls alike, while my brave warriors were befuddled by the eccentric design of innumerable forking corridors and darkened sanctums. But there is more...something which clots my very veins with shame.

Cussurak the Elder, my predecessor as Master of the World, had himself imprisoned the Blackk Gor in the Pit before I was ever conceived. In the early days of his own reign, a deal he had struck with a considerably powerful Dassman: Cussurak granted the ArchDassman an eminent seat in the Warrior Chambers and a ranking office in his army, and in return the ArchDassman sealed the sinister Gor in the Pit with the Art. Under his spell, they were unable to venture past the opening of the cavern, nor could their souls flee their hardened shells save by the sword of a Surcort soldier. And so, whatever grisly murders were enacted on the mountain folk nearby the Pit which caused me to act without due consideration, the Blackk Gor were never responsible.

Had I, in the early days of my reign, taken the time to study the Tome of Rathnic--a task that Cussurak the Younger had always considered a sacred duty--I would have known of this deed. In my blind haste, I emptied the souls of the Gor unto the world...and there seems no way to set things right.

I am old now, the man who was once Master of the World. I am old, and I am ashamed that I have taken to hiding, cowering in the ruins of a mountain village. That the Blackk Gor have not yet slain me is my final punishment, for it has allowed me to witness the prolonged consequences of my lamentable errors. Of what the future holds I am grimly afraid, for the Gor march ever outward now. Their goal seems to be the destruction of all vestiges of mankind. My once beautiful empire will be dust in precious, little time. Even the Dassman and others who practice the Art seem powerless against this strain of Gor, and their numbers dwindle.

Yet, the last Dassman I spoke with told me of a country far to the west, unheard of in my time, with an army of demigods and wisdom which embarrasses the Art. And the Gor have not been seen in these hills, nor in the valley, for an entire moon's cycle, I am told. Perhaps it is ended...I doubt I will live long enough to be certain. This tale, which a loyal scribe is etching into stone, shall be my final task.

May the Creators forgive me.